The Complete Public Wi-Fi Safety Guide: Security, Encryption & Real-World Risks

Public Wi-Fi networks are convenient, but they introduce one of the most common cybersecurity risks for everyday users. Airports, hotels, cafés, malls, schools, and co-working spaces all provide open or lightly protected wireless access. Without proper safeguards, attackers can intercept traffic, capture sensitive data, or redirect unsuspecting users to malicious websites.

This guide explains the technical risks behind public Wi-Fi, how attackers exploit them, and practical steps to stay secure. The explanations use real networking behavior — not marketing terms — to show what is actually possible inside an untrusted network.

Why Public Wi-Fi Is Inherently Unsafe

The problem is not Wi-Fi itself — it is the lack of trust. When a user connects to a public hotspot, they share the same broadcast domain with unknown devices. Every device can theoretically observe broadcast traffic and attempt active attacks. If the network uses outdated encryption or no encryption at all, traffic becomes even easier to read.

Common weaknesses in public Wi-Fi:

- No password or shared password — anyone can join

- No isolation — devices can see each other

- Unencrypted DNS — requests are visible

- Weak router security — outdated firmware, default credentials

- Rogue access points — fake hotspots copying hotel/café names

What Attackers Can Do on Public Wi-Fi

A user may assume that nobody is “watching,” but open networks make surveillance trivial. Attackers do not need physical access — they only need a device connected to the same Wi-Fi zone. With even basic tools, they can perform passive sniffing or active interception.

1. Traffic Sniffing

If traffic is not encrypted, packet capture tools can record login forms, cookies, session tokens, or private messages. Even with HTTPS, some metadata remains exposed, and poorly configured websites may leak data unintentionally.

2. DNS Manipulation

DNS requests leave the device first, translating domain names into IP addresses. If DNS is unencrypted, a malicious hotspot or compromised router can spoof responses. This results in silent redirection — for example, directing users to a fake banking site that looks identical to the real one.

3. SSL Stripping

On weak networks, attackers attempt to downgrade HTTPS to unencrypted HTTP. Modern browsers include protections, but misconfigured sites and expired certificates still open the door to interception.

4. Rogue Access Points

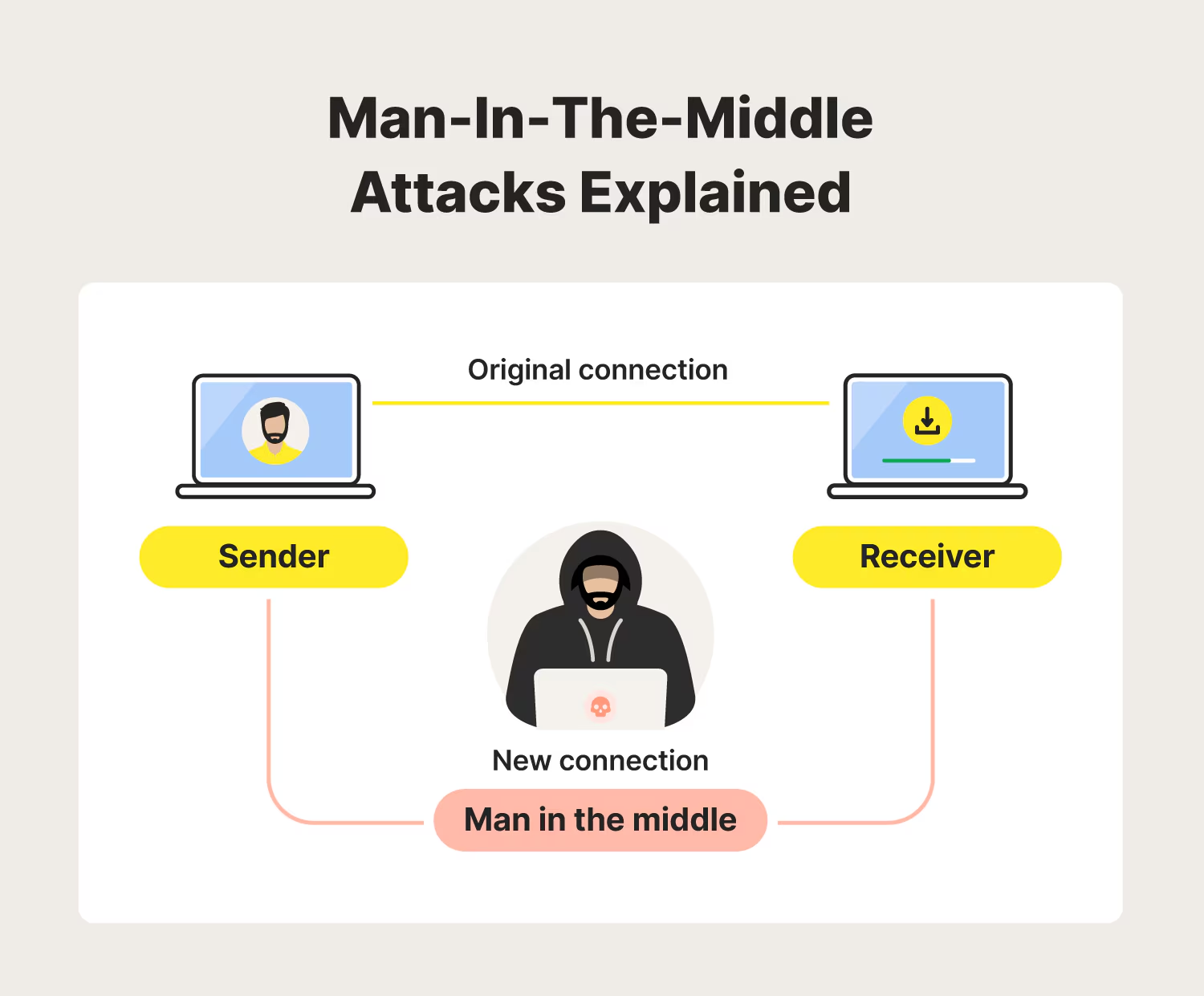

A fake hotspot with the same name as “Airport Free Wi-Fi” or “Hotel Guest Network” can capture all traffic from users who automatically connect. Once connected, attackers act as the gateway, enabling MitM (Man-in-the-Middle) attacks.

How VPNs Protect Users on Public Networks

A VPN creates an encrypted tunnel between the device and a remote server. Even if the hotspot owner or a nearby attacker tries to snoop, the content of the connection remains unreadable. Importantly, DNS queries and IP traffic also move inside the encrypted tunnel.

In practice, this prevents:

- Rogue hotspot data capture

- ISP or router operator monitoring

- Unencrypted DNS exposure

- Forced HTTP redirection

- Simple packet sniffing attacks

When a VPN is active, a public Wi-Fi network behaves only as a transport path. The attacker sees an encrypted stream, not the websites visited or data transmitted.

HTTPS Still Matters

Even with a VPN, HTTPS is essential. HTTPS prevents data exposure on the destination side and protects against server-level tampering. If the VPN fails or disconnects, HTTPS ensures that confidential data is not sent in plain text. This layered defense is why modern browsers enforce HTTPS warnings aggressively.

Modern Protections: Secure DNS, HSTS, and Browser Controls

Newer privacy technologies add additional layers:

- DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH): encrypts DNS queries

- HSTS: prevents SSL stripping

- Certificate pinning: ensures correct destination identity

Even with these protections, the safest practice on untrusted Wi-Fi is tunneling everything through a VPN.

When a VPN Helps Beyond Wi-Fi

Public Wi-Fi risks apply to more than cafés and airports. Many hotels use shared networks without isolation. Corporate guest Wi-Fi often places every visitor on the same subnet. University networks may allow peer-to-peer visibility. In each case, a VPN prevents other guests or endpoints from inspecting unencrypted traffic.

Real-World Example: Airport Networks

Airport hotspots frequently require captive portals. Some force browsers to a non-HTTPS landing page, exposing users before encryption begins. Attackers mimic these portals to steal authentication cookies or social logins. With a VPN connected before browsing, the landing page is displayed through the tunnel, reducing interception risk.

Testing Your Setup

Users can test whether their VPN protects DNS and IP traffic by checking their public address, leak status, and DNS resolvers.

Our VPN tools page lists IP and DNS testing utilities that help verify configuration after connecting to public Wi-Fi.

Best Practices for Safe Public Wi-Fi Usage

- Always connect to the VPN before browsing

- Avoid login or banking sessions without encryption

- Turn off file sharing and printer sharing

- Use HTTPS-only mode when available

- Forget networks after use to avoid auto-reconnect

Final Summary

Public Wi-Fi is convenient, but by design it is not trustworthy. Attackers can silently capture traffic, redirect DNS, impersonate hotspots, or inject malicious content. A VPN creates a secure, encrypted path out of the untrusted network, denying attackers access to browsing activity and data. Combined with HTTPS and basic device hygiene, it transforms unsafe networks into usable ones — without exposing sensitive information.